+Introduction

Introduction to the Religious History of Carlow

Carlow and its immediate surrounds contain a number of ecclesiastical sites which can be deemed to be of national significance. These include the monastic site at St. Mullins, the Romanesque doorway at Killeshin, the medieval Cathedral of Old Leighlin, the eighteenth-century College and the nineteenth- century Catholic cathedral in Carlow and the exquisite Adelaide memorial chapel at Myshall. These sites are included on the trails and in some ways can be deemed the ‘highlights’.

The intention, however, has also been to take in examples of less well-known sites, to bring visitors to parts of the county that are less-travelled and introduce them to places which have an equally important position in the ecclesiastical history of the county. These are often places which have attracted local visitors for centuries if not millennia as in the holy well sites. Some places are associated with famous people and their births or deaths. A visit to the O’Meara tomb in Bennekerry will introduce the visitor to a famous Carlow artist while several sites are associated with Cardinal Patrick Moran, a native of Leighlinbridge. The Quaker burial grounds in the Fenagh and Ballon areas remind us that the county included communities whose belief systems operated outside the mainstream Catholic and Church of Ireland faiths.

Some sites are included purely because their landscape setting and general atmosphere engender a sense of spirituality. The isolated Temple Moling, a site with only ephemeral remains and associations, can surely be considered a valid expression of the ecclesiastical heritage of Carlow.

The oldest sites with ritual or religious significance are probably the holy wells, of which Carlow has a large number. Many bear the names of early Christian saints and are sited close to early monasteries but may have been visited for centuries prior to the coming of Christianity when ritual significance was attached to their water or their location. The holy wells at Clonmore, Old Leighlin, Cranavane, Killoughternane and St. Mullins are included in these trails. All are situated in tranquil surroundings and are well maintained by the many local people who appreciate the long traditions of spirituality and healing associated with them.

Christianity was firmly established in the Carlow area in the late fifth century following the evangelising work of St. Iserninus and the baptism by St. Patrick of Crimthann, King of Leinster. This baptism took place c. 450 at Rathvilly, reputedly at the spot now marked by St. Patrick’s Well. In the ensuing decades, followers of St. Patrick set up monasteries across what is now County Carlow and its environs. St. Fiach founded the monastery at Sleaty and St. Fortiarnán (Fortchern) founded Killoughternane, both places being regarded as significant missionary schools. Schools such as these trained young men who then spread Christian teachings throughout Europe. St. Willibrord, originally from Northumberland, came to study at the monastery of Clonmelsh in Garryhundon, Co. Carlow. In 690 he embarked on a mission to the Low Countries where he became Bishop of Utrecht and national saint of Luxembourg, St. Columbanus who founded many religious settlements across Europe also had Carlow associations and is believed to have been born in the Myshall area.

In the seventh century, important monasteries were founded by Saints Goban and Laserius at Old Leighlin and by Moling at St. Mullins. The timber buildings associated with these early foundations have disappeared but the remnants of later stone churches and high crosses survive. These churches are often diminutive but skilfully constructed as at Agha and Killoughternane and occasionally they delight with magnificent Romanesque carving as at Killeshin and Ullard. The base of one round tower survives at St. Mullins, but towers survived at Kellistown and Kellishin up to recent centuries and there may also have been examples at Lorum and Clonmore. When we add to the catalogue the high crosses, both decorated and plain, surviving at Clonmore, Old Leighlin, Nurney, St. Mullins, Graiguenamangh and Ullard, we can appreciate Carlow’s remarkably rich, early medieval ecclesiastical heritage.

The twelfth century was a period of great change, seeing the arrival of continental monastic orders, the decline of many of the older monastic foundations, the organisation of a diocesan and parochial structure and the invasion of Ireland by the Anglo-Normans in 1169. Leighlin was formally instituted as a diocesan centre in 1111 and construction of the cathedral church at Old Leighlin began in the late twelfth century. This beautiful building, still in use for worship, retains much of its medieval fabric. When the Anglo-Normans colonised Carlow they gravitated towards the ancient monastic sites where they set up their parish churches and residences. The importance of church sites can be seen in the placement of mottes – earthwork castles – at locations such as St. Mullins, Clonmore and Killeshin.

Remains of medieval parish churches survive at Anglo-Norman manorial centres like Wells, Kellistown and Dunleckny, reminding us that north Carlow was particularly densely settled by tenant farmers from England and Wales in the thirteenth century.

William Marshall, Lord of Leinster, founded a Cistercian house by the waters of the Duiske stream at Graiguenamanagh c. 1204, and one of the best preserved monastic churches in Ireland can be visited here. This church is still in use for its original purpose as is the cathedral of Old Leighlin, the oldest working building in Co. Carlow. The first Carmelite house in Ireland was founded in Leiglinbridge c. 1270 and while no remains are now visible, the location of this house, by the strategic Barrow Bridge can still be appreciated.

Another major milestone in the ecclesiastical history of the county came in the sixteenth century with the Reformation. The monastic houses were dissolved and their property distributed among the landed class. Parish churches became Protestant but most fell into disrepair due to the majority of parishioners retaining their Catholic faith. The severe restrictions placed on Catholic worship by the Penal Laws saw the emergence of what might be termed ‘non-standard’ places of worship. Mass rocks survive in many places and small Penal chapels, often built of mud and daub, were built in sacred areas like graveyards and old monastic cloisters.

The lifting of the Penal restrictions in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, coupled with rising population levels saw a massive resurgence in Catholic church building. Bishops of the Catholic Diocese of Kildare and Leighlin such as James Keeffe, Daniel Delane and James Doyle played major roles in the struggle for Catholic Emancipation and were the driving forces behind the construction of a series of new buildings and the introduction of new religious orders. Carlow College was founded in 1782 to train young men for the professions and the ministry, while work on Carlow Cathedral began in 1828 – the year before the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act. The noted architect Thomas Cobden was involved in both buildings and the resulting structures sent out both spiritual and aesthetic signals. Across the county a range of smaller parish churches were built ranging from plain barn-style churches such as that at St. Fintan’s Ballinabranagh to the more ornate neo-Gothic style of which St. Patrick’s Newtown is a fine example. These churches, in their dedications, stained glass and funerary monuments paid tribute to the early saints who built the first places of worship in the county.

The Church of Ireland also witnessed a greatly accelerated building campaign in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The Board of First Fruits, the official regulating body with responsibility for building for what was then the Established Church, financed the erection of many churches across the county. These churches, Nurney and Lorum are good examples, were characterised by elegant lines and graceful spires which often can be seen from afar. Their interiors were frequently austere with decoration kept to a minimum. In contrast, the Church of Christ the Redeemer (the Adelaide Memorial Church) built as a memorial chapel adopted a very ornate neo-Gothic style with an interior filled with striking examples of iron and stone work.

Carlow’s ecclesiastical sites thus span at least fifteen centuries and faithfully reflect the county’s religious and cultural history over that time. They also constitute a key part of the county’s landscape and identity and thus command our attention and respect in the twenty-first century.

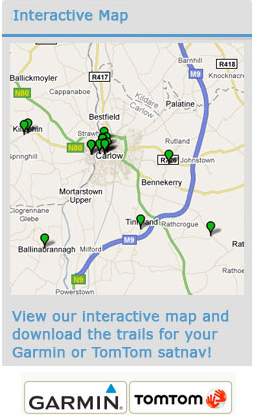

To download the brochure “Carlow – Trails of the Saints” please click here